A Control Engineer’s view of the Three Lines of Defence (Part 2)

Introduction

In the earlier note we looked at the Three Lines of Defence (3LoD) through a control engineering lens to provide a context for some of the practical challenges that financial services organisations are experiencing with the framework.

In this note we look at how control engineering design principles can be applied to the 3LoD framework to yield a better overall design. Specifically, I want to look at three challenges for 3LoD frameworks to see how control engineering principles can help:

- The unhealthy tension between the lines of defence how to achieve a better balance.

- Data overload – how to approach data/information flows in the 3LoD.

- Emerging risks – how to anticipate and adapt but not overreact to the changing risks in the environment.

The unhealthy tension: Are you a spring or a damper?

One of the simplest passive control systems that exists is a car suspension system (see Figure 1) otherwise referred to as a mass-spring-damper. The combination of the spring and damper (shock-absorber) operates to insulate the car from bumps in the road. The spring stores and returns energy to offset the forces from the road surface while the damper dissipates energy to reduce the oscillations that would occur if the spring was used alone.

To a certain extent the spring and damper operate in opposition to each other but the combination is ‘tuned’ to provide a level of comfort for the occupants of the car over a range of road surfaces.

The same concept is evident in the overall 3LoD framework, where the combination of the three lines (particularly the first and second) should result in balanced outcomes for the organisation. This simple analogy also highlights two of the key challenges faced in achieving this:

- Though the first line will tend to drive business, i.e. operate as a ‘spring’, and the second line will challenge, i.e. operate as a ‘damper’, neither line is purely one or the other. So, for example, second line functions have a business development as well as monitoring role to play.

- However, groups and individuals find it difficult to operate in a middle-ground – there is always a tendency to go one way or the other.

I would argue that the typical approach, based on ‘tension’ between the first and second lines, has morphed from one in which the drive to do business held too much sway to one in which the oversight and policing have become overemphasised.

So what can be done about it?

Like any effective control system, the lines of defence need to be reconfigured, or tuned, to operate successfully. But what does this mean in practice and who is going to do this? The tuning aims to achieve the desired output performance – think sport mode versus comfort mode in your car – as well as balancing performance with overall efficiency (e.g. fuel consumption). Unfortunately, ‘self-tuning’ by individual departments tends to lead to an exacerbation of existing behaviours. To counter this, in some organisations, second line functions like Compliance have reconfigured their activities between surveillance and advisory and, in some cases, moved advisory activities into the first line.

One of the more effective approaches I have seen has been the use of embedded senior risk managers in the first line. These were typically senior product line managers moved into a risk role (and ‘relieved’ of their revenue generating responsibilities) meaning that they have both the experience and the seniority to make the necessary judgement calls. The fact that this model was more common in the partnership era of investment banking, where the owners of the business also had their personal wealth tied up in the firm, adds credence to its efficacy.

Some control systems tune themselves by continuously optimising a cost function which is effectively an equation containing the factors (tracking error, energy usage etc.) to be ‘balanced’. One of the challenges with applying this approach to the 3LoD is that generally the risk parameters are less easily quantified especially in relation to operational risk areas. In addition, the ongoing financial cost is rarely quantified[1]. Despite this, the concept of actively managing a cost function which balances the risk and running costs is a useful one, even where it may be as much a qualitative as quantitative activity.

Who then should be responsible for managing the cost function and ultimately tuning the framework? My personal view is that Group Operational Risk and the governance processes they support are best placed to do this. They already have half the equation in the form of the aggregated risk measures (in whatever form they take) and, in contrast to other second line groups, should have a broader view of the operational risk landscape and associated costs in the organisation.

Data overload: Use it or lose it

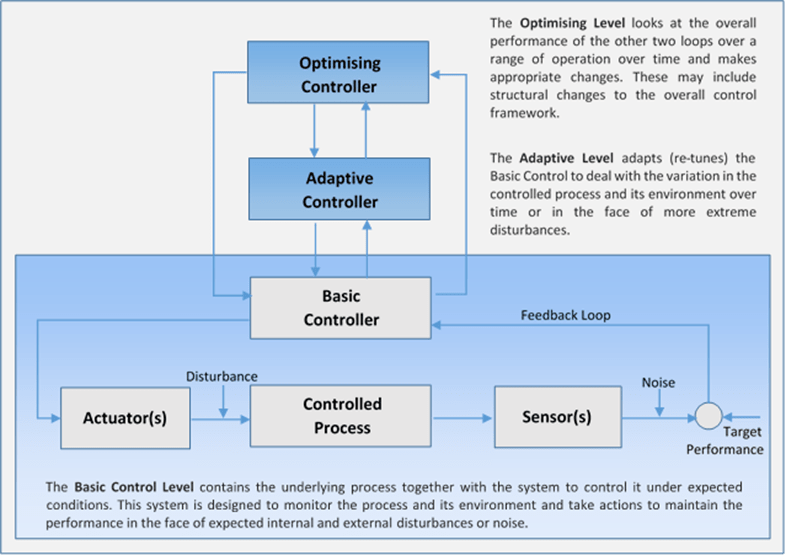

The second area of challenge widely reported by businesses and first line of defence groups is the increasing demand for data. Developments like the Senior Managers Regime (SMR) are increasing the personal accountability of senior management in financial services. This is leading to a greater desire for information across the organisation which, while in many respects a positive development, once again has proved difficult to implement in an efficient manner. Providers of information complain of the significant additional burden of generating the various reports requested, while recipients complain of information overload. Developments like big data have fuelled a tendency to gather more data in the hope of eliciting new insights. It could be argued that the ‘data issue’ is in fact just another symptom of the lack of clear design around the interaction of the lines of defence. Again control systems design has some insights that can provide guidance in this area. In particular, hierarchical control systems where the control loops are organised in a hierarchy similar to the management structures in organisations. The concepts have been around for more than 40 years[2] and are widely used in manufacturing and robotic control systems. Figure 2 shows a simple hierarchical control system formed of three layers: – basic control, adaptation and optimisation.

There are many principles involved in the design of hierarchical control systems but two of the most fundamental ones are:

- Each higher layer of the hierarchy operates with a longer interval of planning and execution time than its immediately lower layer.

- The lower layers have local tasks, goals, and sensations, and their activities are guided by higher layers which do not generally override their decisions.

In essence, each layer of a hierarchical control system views the layer(s) below it as the system to be measured and controlled rather than looking through it to the underlying process. This is an important point because it emphasises that the ‘upper’ layers need to work with and through the business processes. To put it more colloquially it is the difference between telling the chef what you want them to cook and leaning over their shoulder adding ingredients directly to the pot. At the same time, however, it requires a degree of understanding of their practical constraints to know what is achievable. I would argue that this is what is missing from a lot of recommendations originating from the second line and third line in today’s 3LoD models – there is a tendency to dictate direct process changes in spite of rather than in light of the impact of those changes on existing business processes.

The model also provides pointers to the data flow between the layers. In line with the principles above, it highlights that the upper layers need to look at and respond to measurements of the basic controlled system and not so much the underlying ‘process plant’. This means in practice that there should be more focus on the quality of business supervision and the extent to which it is achieving its performance objectives as opposed to duplicating business process measures. To take a simple example from my own experience, it is the difference between reviewing trade breaks each month versus focussing on the trend in trade breaks over several months. Some firms have started to do this through the use of dashboards and ‘traffic lights’ although any measures are only as good as the thought that has gone into them.

In my experience, 90%+ of data that was gathered in operational risk reports is never used to drive any decisions or actions outside of the area that generated it. No engineering control system would be built in this way. It is far better to gather a smaller set of relevant data attributes along the lines described above and make use of it. Organisations should therefore review the information they are escalating to understand better how they are using it and importantly what actions they would take on the back of it. Any data without an associated action should be challenged.

Similarly, first line and business groups complain that they spend a significant amount of time re-mapping items into taxonomies that reflect the way that individual second or third line groups want to see the information rather than using a view that reflects the nature of the business. While superficially appealing, this ‘normalisation’ in the absence of an appreciation of the business flows and their complex interactions can itself introduce gaps into the overall control framework in addition to the significant workload that arises from maintaining multiple views for different stakeholders including regulators.

Another challenge is that the same reporting mechanisms tend to be used for escalation despite the fact that this is a very different situation. The first is about the monitoring the ongoing health of the business while escalation is about rapid communication of specific issues. Clearly there is potential correlation between the two, i.e. an area with chronic performance issues may have a greater frequency of escalations, but to use the same control processes for both is like using normal operating plans for BCP situations. Firms therefore need to think explicitly about the control processes around escalations, specifically the quantitative and qualitative triggers for escalation, the audience and actions.

Emerging risks: avoiding the knee-jerk reaction

The hierarchical model also lends itself to the thinking about the approach to emerging risks, for example cyber-crime which has become a significant threat in recent years. Clearly, processes and controls designed a number of years ago may have deficiencies in relation to cyber-threats and need to be changed. This is a specialised area of risk and there may not be expertise around it in the business unit or first line, at least initially. This is where the role of the second line specialist areas as the ‘adaptation’ mechanism in the overall system become important. Second line functions should continuously scan the environment for developments in their areas of expertise and work through the operational risk governance processes and with the relevant stakeholders to determine how the affected business processes can best be adapted. As was mentioned in the earlier paper, there is a tendency instead to dictate bolt-on controls with little or no notice to the business often resulting in a significant and unnecessary deterioration in efficiency and/or customer service. My personal view is that this is because many second line functions are not sufficiently proactive in scanning for and considering new risks and instead react aggressively to risks once they arise. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, they should spend less time obsessing about the known-knowns and more time identifying the known-unknowns and the unknown-unknowns[3].

At the same time adaptation is not the exclusive responsibility of the second line. New business activities can bring new risks and challenges, for example the growth in algorithmic trading. It is important that product / business approval processes and committees bring together the business, first line and second line groups in a constructive risk assessment process incorporating external (e.g. regulatory) input as appropriate. Note the emphasis here is on constructive – if the participants take polarised perspectives on the product risks and there is no meeting of minds then that is unlikely to result in a well-designed set of controls.

Conclusions: the Elephant in the Room and the role of Internal Audit

So far I have steered clear of a very important aspect of the design of the 3LoD which is the inherent principal-agent relationship between the business unit and the board, and ultimately the firm and external stakeholders[4] and the potential misalignments of interests that can arise. Post the Financial Crisis, this issue has underpinned the design of a lot of regulations. It would be remiss therefore to ignore this challenge, but it is equally true that the issue should not become a licence for ignoring all other aspects of good control design.

Most engineering control design assumes that sensors are providing reliable and accurate information and most actuators are similarly acting on instructions reliably[5]. The same cannot be said in financial services. There is no doubt (and there is plenty of historical evidence support this) that personal incentives are a significant driver of behaviour. However, taken to extreme, agency theory inexorably means you end up operating as if your staff, customers and suppliers are all lying to you all the time. This then becomes the dominant design parameter for business processes and the myriad of additional controls introduced tend to fragment existing business processes into silos with significant impacts on efficiency and customer service. In fact, this fragmentation may result in muted benefit from the additional controls as the end-to-end understanding and visibility of the activity is lost.

Against this backdrop, how is the Board to be comfortable that the 3LoD is operating effectively and efficiently? I think that most people would see this as the responsibility of Internal Audit given the role the group plays in providing independent assurance around the organisation’s risk management[6]. I would argue that most audit teams need to complement their micro-assessment of individual risks and controls with a more holistic assessment of the efficacy of the overall (3LoD) control framework including whether it represents value is for money. To be clear, this is not about reducing the amount of money spent on controls but rather for a given (and often significant) expenditure are the Board really getting the level of assurance they should expect. I would argue in most cases not.

[1] With the exception of the regulatory capital charge which is itself derived from the risk measure

[2] Hierarchical Control Systems, An Introduction, W. Findeisen, April 1978

[3] Donald Rumsfeld, Department of Defense news briefing, 12 February 2002

[4] Investors, clients, regulators, suppliers and ultimately the wider public.

[5] Even then there is a branch of control called fault tolerant control which deals with these types of situations

[6] The Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors defines the role of Internal Audit as “to provide independent assurance that an organisation’s risk management, governance and internal control processes are operating effectively”.